Buddha, Meditation, Medicine

„Die Mittleren Stufen der Meditation“

>> Acharya Kamalashila <<

und

„Die Mittleren Stufen der Meditation“

Kamalashila war ein indischer Pandita. Er lebte im 8. Jahrhundert und war Schüler des Acharya Shantarakshita. „Pandita“ (Skr.) bedeutet „Gelehrter“, „Acharya“ (Skr.) bedeutet „Leiter des Studiums, Lehrer“.

Der tibetische König Trison Detsen (742-496) hatte Padmasambhava eingeladen, damit er in Tibet den Buddhismus verbreite. Als sie entschieden, auch ein Kloster zu gründen – das Kloster Samye südlich von Lhasa – luden sie den Mönch Shantarakshita ein. Dieser gab die Mönchsgelübde und erteilte für längere Zeit Unterweisungen.

Shantarakshita sagte: „Wenn Ihr künftig einen maßgeblichen Meister bei Euch haben wollt, solltet Ihr meinen Schüler Kamalashila einladen.“

Als ein großer chinesischer Meister nach Tibet kam und seine Lehrmeinung verbreitete, lud Trison Detsen Kamalashila ein. Es kam zu einer großen Disputation zwischen den beiden Meistern. Shantarakshitas Lehrmeinung konnte aufrechterhalten werden, die chinesische Lehre wurde nach China zurück geschickt.

YOGA IM BUDDHISMUS

*

> The Eight-Fold Path Of Bhagwan Buddha <

Compiled by: Prabhat Tiwari

Lord Buddha was a contemporary of Maharshi Patanjali, the propagator of the ‘Yoga Darshana’. Just as Patanjali suggested that yoga has eight steps (ashtanga yoga) with a final goal as ‘samadhi’, Buddha too has suggested eight steps to ‘samadhi’. – Editor

Buddha says, “Wrongs are many, right is one, so how can the right be against the wrong? Right is that which is not your invention. It is already there. If you go away from it you are wrong, if you come close to it you are right. The closer you are, the more right you are. One day, when you are exactly home, you are perfectly right.”

Samyak and samadhi both start with the same root sam (equal). Samyak is the step towards samadhi. So seven steps ultimately lead to the final step ‘samadhi’. ‘Samadhi’ means – now everything has fallen in tune with existence.

These eight steps are just indicators of how to come to that ultimate courage where you take the quantum leap and you simply disappear. When the self disappears, the Universal Self arises.

> The Noble Eightfold Path < describes the way to the end of suffering, as it was laid out by > Siddhartha Gautama < . SiddhÄ�rtha Gautama (Sanskrit, m., सिद्धार्थ गौतम, SiddhÄ�rtha Gautama; Pali: Siddhattha Gotama) was a spiritual teacher in the north eastern region of the Indian subcontinent who founded Buddhism.

It is a practical guideline to ethical and mental development with the goal of freeing the individual from attachments and delusions; and it finally leads to understanding the truth about all things. Together with the Four Noble Truths it constitutes the gist of Buddhism. Great emphasis is put on the practical aspect, because it is only through practice that one can attain a higher level of existence and finally reach Nirvana. The eight aspects of the path are not to be understood as a sequence of single steps, instead they are highly interdependent principles that have to be seen in relationship with each other.

* Buddha mit seinen ersten 5 Schülern unter dem Bodhi Baum, Pappel-Feige (Ficus religiosa), auch Buddhabaum, Bobaum oder Pepul-, Pepal-, Pipul- oder Peepalbaum.

Buchtipp: Ringu Tulku, Ri-Me Philosophy

> The Ri-me Philosophy of Jamgon Kongtrul the Great: <

A Study of the Buddhist Lineages of Tibet

This compelling study of the Ri-me movement and of the major Buddhist lineages of Tibet is comprehensive and accessible. It includes an introduction to the history and philosophy of the Ri-me movement; a biography of the movement’s leader, the meditation master and philosopher known as Jamgön Kongtrul the Great; helpful summaries of the eight lineages‘ practice-and-study systems, which point out the different emphases of the schools; an explanation of the most hotly disputed concepts; and an overview of the old and new tantras.

Rimé is a Tibetan word which means „no sides“, „non-partisan“ or „non-sectarian“. In a religious context, the word ri-mé is usually used to refer to the „Eclectic Movement“ between the Buddhist Nyingma, Sakya, and Kagyu traditions, along with the non-Buddhist Bön religion, wherein practitioners „follow multiple lineages of practice.“ The movement was founded in Eastern Tibet during the late 19th century largely by Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo and Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Thaye, the latter of whom is often respected as the founder proper. The Rimé movement is responsible for a large number of scriptural compilations, such as the Rinchen Terdzod and the Sheja Dzö. Read more: > HERE <

* Jamgön Kongtrul the Great (1813–1899) * is a giant in Tibetan history, renowned for his scholarly and meditative achievements, but also for his energetic yet evenhanded work to unify and strengthen the different lineages of Buddhism. The Ri-me movement, led by Kongtrul and several other leading scholars of the time, was a unifying effort to cut through interscholastic divisions and disputes that were occurring between the different lineages. These leaders sought appreciation of the differences and acknowledgment of the importance of variety in benefiting practitioners with different needs. The Ri-me teachers also took great care that the teachings and practices of the different schools and lineages, and their unique styles, did not become confused with one another. This lucid survey of the Ri-me movement will be of interest to serious scholars and practitioners of Tibetan Buddhism.

What is „Rimé“? Ris or Phyog-ris in Tibetan means „one-sided“, „partisan“ or „sectarian“. Med means „No“. Ris-med (Wylie), or Rimé, therefore means „no sides“, „non-partisan“ or „non-sectarian“…..

Ri-Mé_Approach, Ringu Tulku, Brussels June 2006, The Ri-Me Philosophy of Jamgon Kongtrul the Great: A Study of the Buddhist Lineages of Tibet by Ringu Tulku, ISBN 1-59030-286-9, Shambhala Publications

…..It does not mean „non-conformist“ or „non-committal“; nor does it mean forming a new School or system that is different from the existing ones. A person who believes the Rimé way almost certainly follows one lineage as his or her main practice. He or she would not dissociate from the School in which he or she was raised. Kongtrul was raised in the Nyingma and Kagyu traditions; Khentse was reared in a strong Sakyapa tradition. They never failed to acknowledge their affiliation to their own Schools.

In the 1970’s I was doing research work on the Rimé (Wylie, Ris-Med ) Movement. This gave me the opportunity to meet and interview a number of prominent Tibetan Lamas, including His Holiness, the Dalai Lama, and the heads of the four main Schools of Tibetan Buddhism. I prepared a questionnaire. One of the questions I asked was whether they believed that other Schools of Buddhism showed the way to attain Buddhahood. I have never been so rebuked in my life as when I asked that question! All of them, without exception, were shocked and felt insulted, deeply saddened that I, a monk, could ever have such doubts. They would not speak with me until I persuaded them to believe that this was one of those unimportant, procedural questions that are part of the modern University system.

„How can you say such a thing?“ they rebuked me. „All Schools of Buddhism practise the teachings of the Lord Buddha. Moreover, the Schools of Buddhism in Tibet have even more common ground. They all base their main practice on Anuttara Tantra of Vajrayana. Madhyamika is their philosophy; they all base their monastic rules on the Sarvastivadin school of Vinaya.

One of the unique features of Buddhism has always been the acceptance that different paths are necessary for different types of people. Just as one medicine cannot cure all diseases, so one set of teachings cannot help all beings – this is the basic principle of Buddhism.

His Holiness, XIV Dalai Lama, has been strongly influenced by some great Rimé teachers such as Khunu Lama Tenzin Gyatso, Dilgo Khentse Rinpoche and the 3rd Dodrupchen Tenpe Nyima. Due to their efforts in recent years, there has been more interchange of teachings amongst different Schools of Tibetan Buddhism than ever before. Following the traditions of Rimé, the Dalai Lama has been receiving and giving teachings of all Schools in their respective traditions and lineages.

Brief History of Dzogchen

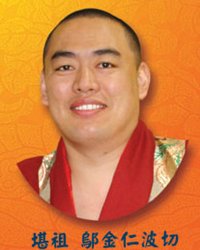

Khentrul Ogyen Rinpoche:

Brief History of Dzogchen

Dzogchen (rdzogs-chen), the great completeness, is a Mahayana system of practice leading to enlightenment and involves a view of reality, way of meditating, and way of behaving (lta-sgom-spyod gsum). It is found earliest in the Nyingma and Bon (pre-Buddhist) traditions.

Bon, according to its own description, was founded in Tazig (sTag-gzig), an Iranian cultural area of Central Asia, by Shenrab Miwo (gShen-rab mi-bo) and was brought to Zhang-zhung (Western Tibet) in the eleventh century BCE There is no way to validate this scientifically. Buddha lived in the sixth century BCE in India.

The Introduction of Pre-Nyingma Buddhism and Zhang-zhung Rites to Central Tibet

Zhang-zhung was conquered by Yarlung (Central Tibet) in 645 CE. The Yarlung Emperor Songtsen-gampo (Srong-btsan sgam-po) had wives not only from the Chinese and Nepali royal families (both of whom brought a few Buddhist texts and statues), but also from the royal family of Zhang-zhung. The court adopted Zhang-zhung (Bon) burial rituals and animal sacrifice, although Bon says that animal sacrifice was native to Tibet, not a Bon custom. The Emperor built thirteen Buddhist temples around Tibet and Bhutan, but did not found any monasteries.

This pre-Nyingma phase of Buddhism in Central Tibet did not have dzogchen teachings. In fact, it is difficult to ascertain what level of Buddhist teachings and practice were introduced. It was undoubtedly very limited, as would have been the case with the Zhang-zhung rites.