HERMANN HESSE FOUNDATION – SIDDHARTHA

(HERMANN HESSE FOUNDATION – Film Footage, Portrait, Sound…)

> THE DIGITAL GUTENBERG PROJECT <

> JNANA YOGA, BHAKTI YOGA, ADVAITA VEDANTA <

Buddha Shakyamuni – Kopf einer Buddhastatue am Niederrhein. Hesse gab der Hauptfigur seiner „indischen Dichtung“ denselben Vornamen des historischen Buddhas Siddhartha Gautama. „Einen Buddha zu schaffen, der den allgemein anerkannten Buddha übertrifft, das ist eine unerhörte Tat, gerade für einen Deutschen.“ > Henry Miller < über Hesses Siddhartha.

Hermann Hesse (German pronunciation: [ˈhɛʀman ˈhɛsə]) (July 2, 1877 – August 9, 1962) was a German-born Swiss poet, novelist, and painter. In 1946, he received the Nobel Prize in Literature. His best-known works include Steppenwolf, Siddhartha, and The Glass Bead Game (also known as Magister Ludi), each of which explores an individual’s search for authenticity, self-knowledge and spirituality. Read More: > HERE <

Hermann Hesse was born on 2 July 1877 in the Black Forest town of Calw in Württemberg, Germany. Hesse began a bookshop apprenticeship in Esslingen am Neckar, but, after three days, he left. Then, in the early summer of 1894, he began a 14-month mechanic apprenticeship at a clock tower factory in Calw. The monotony of soldering and filing work made him resolve to turn himself toward more spiritual activities. In October 1895, he was ready to begin wholeheartedly a new apprenticeship with a bookseller in Tübingen. This experience from his youth he returns to later in his novel Beneath the Wheel.

In Gaienhofen, he wrote his second novel, Beneath the Wheel, which was published in 1906. In the following time, he composed primarily short stories and poems.

Gaienhofen was also the place where Hesse’s interest in Buddhism was re-sparked. Following a letter to Kapff in 1895 entitled Nirvana, Hesse ceased alluding to Buddhist references in his work. In 1904, however, Arthur Schopenhauer and his philosophical ideas started receiving attention again, and Hesse discovered theosophy. Schopenhauer and theosophy renewed Hesse’s interest in India. Although it was many years before the publication of Hesse’s Siddhartha (1922), this masterpiece was to be derived from these new influences.

During this time, there also was increased dissonance between him and Maria, and, in 1911, Hesse left alone for a long trip to Sri Lanka and Indonesia. Any spiritual or religious inspiration that he was looking for eluded him, but the journey made a strong impression on his literary work. Following Hesse’s return, the family moved to Bern (1912), but the change of environment could not solve the marriage problems, as he himself confessed in his novel Rosshalde from 1914.

In 1931, Hesse began planning what would become his last major work, The Glass Bead Game (aka Magister Ludi). In 1932, as a preliminary study, he released the novella Journey to the East. The Glass Bead Game was printed in 1943 in Switzerland. For this work, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1946.

AWARDS: * 1906 – Bauernfeld-Preis, * 1928 – Mejstrik-Preis der Wiener Schiller-Stiftung, * 1936 – Gottfried-Keller-Preis * 1946 – Goethepreis der Stadt Frankfurt, * 1946 – Nobel Prize in Literature, * 1947 – Honorary Doctorate from the University of Bern, * 1950 – Wilhelm-Raabe-Preis, * 1954 – Orden Pour le mérite für Wissenschaft und Künste, * 1955 – Peace Prize of the German Book Trade

From the end of the 1930s, German journals stopped publishing Hesse’s work, and it was eventually banned by the Nazis.

The Glass Bead Game was Hesse’s last novel. During the last twenty years of his life, Hesse wrote many short stories (chiefly recollections of his childhood) and poems (frequently with nature as their theme). Hesse wrote ironic essays about his alienation from writing (for instance, the mock autobiographies: Life Story Briefly Told and Aus den Briefwechseln eines Dichters) and spent much time pursuing his interest in watercolors.

Hesse also occupied himself with the steady stream of letters he received as a result of the prize and as a new generation of German readers explored his work. In one essay, Hesse reflected wryly on his lifelong failure to acquire a talent for idleness and speculated that his average daily correspondence was in excess of 150 pages. He died on 9 August 1962 and was buried in the cemetery at San Abbondio in Montagnola, where Hugo Ball is also buried.

The Digital Gutenberg Project – In June 2002, the Ransom Center and IImage Retrieval Inc. of Carrollton, Texas collaborated on the digitization of the Center’s Gutenberg Bible using the i2s Digibook 6000 overhead scanner. The project took less than a week to complete and resulted in nearly 1,300 digital images. For the first time, it is possible for the general public to view all of the pages from the University of Texas copy, including all of the large illuminated letters in volume I and the copious handwritten annotations, as well as other indications of the book’s use in religious services. The release of the web images coincides with the installation of the Gutenberg Bible in a new exhibition case, part of the recently remodeled main lobby of the Ransom Center.

Further reproduction of any of the Gutenberg Bible images without the written consent of the Ransom Center is prohibited. Inquiries regarding the availability of higher-resolution digital images for research or publication should be directed to the Center’s staff.

The > Project Gutenberg < Presents Siddhartha > CONTENT < :

Copyright Status: Not copyrighted in the United States. If you live elsewhere check the laws of your country before downloading this ebook.

An Indian Tale by Hermann Hesse:

…..But he, Siddhartha, was not a source of joy for himself, he found no delight in himself. Walking the rosy paths of the fig tree garden, sitting in the bluish shade of the grove of contemplation, washing his limbs daily in the bath of repentance, sacrificing in the dim shade of the mango forest, his gestures of perfect decency, everyone’s love and joy, he still lacked all joy in his heart. Dreams and restless thoughts came into his mind, flowing from the water of the river, sparkling from the stars of the night, melting from the beams of the sun, dreams came to him and a restlessness of the soul, fuming from the sacrifices, breathing forth from the verses of the Rig-Veda, being infused into him, drop by drop, from the teachings of the old Brahmans.

…..For whom else were offerings to be made, who else was to be worshipped but Him, the only one, the Atman? And where was Atman to be found, where did He reside, where did his eternal heart beat, where else but in one’s own self, in its innermost part, in its indestructible part, which everyone had in himself? But where, where was this self, this innermost part, this ultimate part? It was not flesh and bone, it was neither thought nor consciousness, thus the wisest ones taught. So, where, where was it? To reach this place, the self, myself, the Atman, there was another way, which was worthwhile looking for? Alas, and nobody showed this way, nobody knew it, not the father, and not the teachers and wise men, not the holy sacrificial songs!

They knew everything, the Brahmans and their holy books, they knew everything, they had taken care of everything and of more than everything, the creation of the world, the origin of speech, of food, of inhaling, of exhaling, the arrangement of the senses, the acts of the gods, they knew infinitely much—but was it valuable to know all of this, not knowing that one and only thing, the most important thing, the solely important thing?

Surely, many verses of the holy books, particularly in the Upanishades of Samaveda, spoke of this innermost and ultimate thing, wonderful verses. „Your soul is the whole world“, was written there, and it was written that man in his sleep, in his deep sleep, would meet with his innermost part and would reside in the Atman…… (Anm.: Advaita Vedanta).

Marvellous wisdom was in these verses, all knowledge of the wisest ones had been collected here in magic words, pure as honey collected by bees. No, not to be looked down upon was the tremendous amount of enlightenment which lay here collected and preserved by innumerable generations of wise Brahmans.— But where were the Brahmans, where the priests, where the wise men or penitents, who had succeeded in not just knowing this deepest of all knowledge but also to live it? Where was the knowledgeable one who wove his spell to bring his familiarity with the Atman out of the sleep into the state of being awake, into the life, into every step of the way, into word and deed?….

Thus were Siddhartha’s thoughts, this was his thirst, this was his suffering.

Often he spoke to himself from the Chandogya-Upanishad the words: „Truly, the name of the Brahman is satyam—verily, he who knows such a thing, will enter the heavenly world every day.“

Often, it seemed near, the heavenly world, but never he had reached it completely, never he had quenched the ultimate thirst. And among all the wise and wisest men, he knew and whose instructions he had received, among all of them there was no one, who had reached it completely, the heavenly world, who had quenched it completely, the eternal thirst.

„Govinda,“ Siddhartha spoke to his friend, „Govinda, my dear, come with me under the Banyan tree, let’s practise meditation.“

They went to the Banyan tree, they sat down, Siddhartha right here, Govinda twenty paces away. While putting himself down, ready to speak the Om, Siddhartha repeated murmuring the verse:

Om is the bow, the arrow is soul, The Brahman is the arrow’s target, That one should incessantly hit.

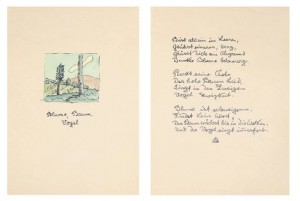

( > * Hermann Hesse Paintings:Flower, Tree, Bird * < )

SIDDHARTHA, FIRST PART

- THE SON OF THE BRAHMAN

- WITH THE SAMANAS

- GAUTAMA

- AWAKENING

SECOND PART

- KAMALA

- WITH THE CHILDLIKE PEOPLE

- SAMSARA

- BY THE RIVER

- THE FERRYMAN

- THE SON

- OM

- GOVINDA

- Related Articles on Yoga, > ADVAITA VEDANTA <

- Meet Hermann Hesse, Friends, Fans, Arts at facebook <

Comments are closed.