Search results for rabindranath (17)

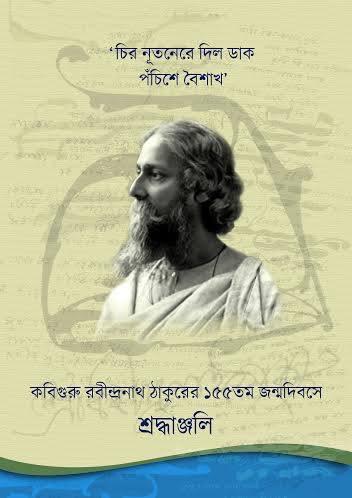

Homage to Rabindranath Tagore on his 155th birthday

Homage to Rabindranath Tagore on his 155th birthday কবিগুরু রবীন্দ্রনাথ ঠাকুরের ১৫৫তম জন্মদিবসে শ্রদ্ধান্জলী

http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/literature/laureates/1913/tagore-bio.html

http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/literature/laureates/1913/tagore-bio.html

Poetry, Rabindranath Tagore in Germany

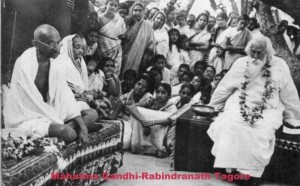

> TAGORE, GHANDI, INDIA TODAY <

> MARTIN KÄMPCHEN & TAGORE BOOK TIPS <

Rabindranath Tagore (Bengali: রবীন্দ্রনাথ ঠাকুর) ,(7 May 1861 – 7 August 1941),γsobriquet Gurudev,was a Bengali polymath. As a poet, novelist, musician, and playwright, he reshaped Bengali literature and music in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As author of Gitanjali and its „profoundly sensitive, fresh and beautiful verse“,being the first non-European to win the 1913 Nobel Prize in Literature, Tagore was perhaps the most important literary figure of Bengali literature and a mesmerising representative of the Indian culture whose influence and popularity internationally perhaps could only be compared to that of Gandhi whom Tagore named ‚Mahatma‘ out of his deep admiration for him.Read More: > HERE <

Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) ist der berühmteste Dichter des modernen Indien. 1913 erhielt er als erster Asiate den > Literatur-Nobelpreis < . Sein universales Genie schuf Literatur in allen Gattungen, er gründete eine Schule und Universität, betätigte sich als Schauspieler, Sänger seiner eigenen Lieder, als Maler und Sozialreformer in den Dörfern. Kämpchen hat als erster Tagore in einer repräsentativen Sammlung von fünfzig Gedichten und Liedern, die alle Schaffensperioden umfassen, den deutschsprachigen Lesern vorgestellt.

Tagore besuchte Deutschland dreimal und wurde dort sehr gefeiert. In mehreren wissenschaftlichen Werken untersucht Kämpchen Tagores Verhältnis zum deutschen Geistesleben der zwanziger Jahre. Dieses letzterschienene Buch beschreibt Tagores Beziehungen zu dem Philosophen Hermann Keyserling, zu Kurt Wolff (seinem Verleger), zu Helene Meyer-Franck (seiner Übersetzerin) und Heinrich Meyer-Benfey (seinem profiliertesten Interpreten).

…..If I were asked who was the greatest poet India has produced, including the greatest of ancient India, Kalidasa, my firm answer would be: ‘Tagore’ … It is tragic, however, that his greatness as a poet will never be generally acknowledged, like the greatness of Goethe, Hugo or Tolstoy…..

These two sentences by the well-known writer Indian > Nirad Chaudhuri < sum up the fate of Rabindranath Tagore as a literary figure: On the one hand, they emphasise the immense importance his work receives in West Bengal and Bangladesh; on the other hand, they demonstrate the clear limits of his importance. Tagore’s influence does not transcend the confines of the Bengali language. Bengali is spoken by approximately 180 million people in West Bengal and Bangladesh. This is a larger figure than, for example, the entire German-speaking population. Yet, Bengali is considered a regional language of the Indian subcontinent (with a limited significance even within the context of the subcontinent), whereas German is accepted as a world language, as indeed most European languages are. We are all aware of the political and economic history which created such an imbalance between the languages and the cultures in the world.

Congenial translations needed!

Hence it entirely depends on the availability of congenial translations whether Rabindranath Tagore’s true worth will be appreciated beyond Bengal. Making Shakespeare, Dante or Tolstoy one’s own with the assistance of excellent translations is comparatively easy. Shakespeare has been translated into German for the last two hundred years with immense success, and is still being translated. But translating Tagore into German does not merely entail two European languages, but two languages which are divided by separate cultures, social contexts, geographical areas and religions. He who wants to translate a poem by Tagore from Bengali to German needs to bridge the gulf which separates India and Germany.

It is not easy for an Indian to admit that their national poet, Rabindranath Tagore, is hardly known in Europe. Although the Indian subcontinent entered the sphere of modern World Literature through Tagore, this has become a fact of history now. Today Tagore is no longer a vibrant, dynamic element of World Literature, he no longer influences the intellectual horizon of a large readership and inspires writers outside Bengal. For Bengalis, Rabindranath Tagore continues to have a powerful, sometimes overbearing cultural presence.

Visiting a youthgroup in Germany, 1930 (siehe oben)

It is virtually impossible to ignore him, even though one may reject him. For Europeans, Tagore represents the distant memory of a Wise Old Man from the East, of an Eastern mystic who arrived in Germany after the First World War to dispense consolation and courage to a people immersed in a deep spiritual and cultural crisis. For less than a decade, Tagore enthused German audiences and readers, after which he sank into oblivion, a process which was aided by the advent of Nazi Germany for which the Indian poet was anathema.

Many Germans may feel that Tagore would best be forgotten. The mystical vagueness of his poems and his lyrical prose may have enthralled European readers for some years, but they could not pass the test of time. These poems were rendered into English by the poet himself and then translated into German by German translators. Tagore’s own English rendering does not merit the term “translation”. These texts were at best paraphrases. He transformed his finely chiselled Bengali verses into rhythmical English prose. In the process he often simplified or even trivialised the content by leaving out some of the more complex ideas and evocations and by adding new material. It is generally agreed that, whatever be the inherent worth of these English texts, they do not echo the intricacy and vigour and musicality of Tagore’s original poetry. Hence I call the German version of Tagore’s poetry “doubly watered-down”: first watered-down by Tagore himself through his English prose texts and then again by adopting them for the German.

If we examine the kind of poems Tagore selected for translation, we realise that they were predominantly his “spiritual” or “mystical” poems. He must have presumed that they especially appeal to Western readers, and he was not mistaken. But in the bargain, Tagore sacrificed a large spectrum of his themes, styles and moods which he did not present to the non-Bengali public. Tagore’s selection of poems helped to reinforce the image of Tagore as a mystic.

With German intellectuals in 1926

With German intellectuals in 1926

In 1921, Rabindranath Tagore visited Germany for the first time. The German people had just suffered a humiliating defeat in the First World War. Burdened with the crushing demands made by the Versaille Treaty, they longed for a “saviour” who could re-establish their self-esteem and help them find again meaning in life. Before entering Germany, Tagore expressed that he empathized with the German people in their hour of crisis and that he had come to strengthen her. So there was a clear symbiotic relationship even before Tagore began his month-long trip from city to city. Tagore mesmerized and fascinated his German audiences. Wherever he spoke, the halls were packed. Indeed, the newspapers reported scuffles and regular fights by people who were refused entry. The German press rose to the occasion by reporting Tagore’s every movement.

Tagore’s poetry had a direct appeal to Germans of that generation because his poetry (or whatever he chose to give to the West) was exotic, had a romantic flair, was imbued with spiritual idealism – and yet in all its strangeness it was still easily accessible. His poetry embodied a religious imagery, essentially Vaishnava in character, which was innovative for Western ears. To them, this culture of emotions was unfamiliar in its directness, its eroticism and involvement with nature and the cosmos – and yet, the poetry was totally comprehensible. Tagore himself, attired in his flowing, dark gown and with his white beard and serene face, radiated a certain erotic energy.

Tagore revisited Germany in 1926 and 1930. Although the early biographies of Tagore characterize Tagore’s three visits to Germany as unmitigated success stories, Tagore himself preferred to take a more detached view. In 1921, he wrote to a friend:

It has been a wonderful experience in this country for me! Such fame as I have got I cannot take at all seriously. It is too readily given, and too immediately. It has not had the perspective of time. And this is why I feel frightened and tired at it and even sad.[2]

The German-speaking press was by no means unanimous in its praise. There were three major points around which the criticism of the press revolved: (1) Tagore, a Hindu, wanted to influence Christians in their faith and ultimately convert them to Hinduism. (2) German writers deserved a slice of the Indian writer’s enormous fame, as they were no less talented and relevant in their writing. (3) Tagore’s seeming “oriental lethargy”, “bloodlessness”, “Indian mildness” was inimical to German or European “dynamism”, to its “action-oriented” mindset. At that point of history, this European mindset was deperately needed to support the reconstruction of the German nation after the First World War.

Rilke, Zweig, Thomas Mann, Hesse

The adulation Tagore received from the masses rather deterred serious German fellow writers from making an evaluation of Tagore’s literary merit. They even shied away from meeting him. Yet, there were two of Germany’s eminent contemporary writers who met Tagore and two others who took a serious interest in him and acclaimed him as a figure of consequence.

Let me first turn to Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926). Even a few months before Tagore was awarded the Nobel Prize, Rilke recognized Tagore’s importance which he expressed in a letter to Lou Andreas-Salomé[3]. Rilke had heard another famous writer, the Frenchman André Gide, read out his French translation of Gitanjali which had impressed Rilke considerably. Further, Rilke mentioned his praise of Tagore in a letter to the German publisher Kurt Wolff[4]. At the time, Wolff had just secured the English manuscript of Gitanjali for his publishing firm and it was already being translated. Quick to see his advantage, Wolff offered to Rilke that he translate Gitanjali into German, as Gide did into French. Rilke considered the offer deeply for some time and then rejected it. This is the explanation he gave in his letter to Kurt Wolff:

I do not find within myself that irrefutable call for the proposed assignment, from which alone could emerge a definitive and responsible work. Although much in these stanzas has a familiar ring, it seems, so to speak, to be borne towards me on a tide of unfamiliarity… This may be partly due to my meagre acquaintance with the English language.[5]

Rilke is not known to have commented on Rabindranath Tagore thereafter, not even in 1921 when the latter was in the zenith of his fame.

Stefan Zweig (1881-1941), the Austrian writer, and Thomas Mann were introduced to Rabindranath Tagore in the summer of 1921. True to their temperament, their reactions to Tagore were quite opposite to each other. Zweig, the suave cosmopolitan and altruistic humanitarian, had visited India in the winter of 1908/09. He was appalled by the poverty and misery he saw and later bemoaned the feeling of “unsurmountable unfamiliarity”[6] that overcame him when he faced India’s tumultuous life. Yet, he maintained an active interest in India’s freedom struggle and in her intellectual life. He also observed Rabindranath’s rise to fame in Europe and exchanged views on him with that other European intellectual with a keenly critical and supportive interest in India, Romain Rolland. So when Kurt Wolff informed Stefan Zweig that Tagore was to change trains in Salzburg en route to Vienna, Zweig who resided in Salzburg, jumped at the chance to meet him. The short meeting was deeply meaningful to Zweig. Returning home, he immediately penned a letter to Wolff in which he wrote:

Thank you very much for the information regarding Tagore’s travel programme. This enabled me to spend half an hour in his company today at Salzburg railway station while he changed trains. Thanks to you, I have encountered this great personality, of whom I formed a strong and profound impression.[7]

Zweig continued to observe Tagore’s impact on the European public. Zweig unequivocally appreciated Tagore’s message of humanism, while he was critical of Tagore’s ostensible penchant to seek publicity. When Tagore chose to visit the philosopher Count Hermann Keyserling in Darmstadt for a week, Zweig commented that Tagore “was unwise enough to have his visit publicly announced”[8]. And in 1926 Zweig criticised Tagore for this “new mania of travelling around Europe as a missionary of the spirit” which he calls a “contageous disease”[9].

Thomas Mann (1875-1955) was both less sympathetic and more complex in his reaction to Tagore. Initially, he even refused to meet him. In 1921, Mann was approached by Hermann Keyserling to write an essay on Tagore which was meant to publicize the “Tagore-Week” Keyserling planned in Darmstadt. Mann refused and was also unwilling to go and attend Tagore’s lectures. In a letter typical of Thomas Mann, he explained the reasons for his negative response.

Dear and Respected Count Keyserling,

I cordially thank you for your letter. It exudes so much enthusiasm that I almost packed my bags and went to Darmstadt. However this would have been easier than writing an article, particularly one canvassing for the famous Indian of whom I have, whether you believe it or not, no understanding, or almost none, until now. […] The image I have always had of him is picturesque but pallid. Surely I do him an injustice in assuming that the subjective pallor of this image reflects reality; in presuming him to be a typical Indian pacifist, animated by a somewhat anaemic humanitarian spirit and a mildness which I deemed almost hostile in the years I spent engrossed in violent emotional conflict. Surely the man is totally different. Since I understand from your letter that he has made a deep impression on you, he must be great.[10]

Thomas Mann alluded to the well-known duality between European strength and Indian “pallor”, “mildness” to which he gave a distinctly negative connotation. The letter was cleverly crafted. Mann had his say on Tagore clearly and then made a rhetorical volte-face by declaring: “Surely the man is totally different. Since […] he has made a deep impression on you, he must be great.” In this manner, he could pronounce his reservations and still hope not to offend the famous Count.

A few weeks later, however, Thomas Mann was unable to avoid coming face to face with the “pallid” Indian poet. Mann lived in Munich and Tagore arrived in that city for several lecture engagements. Tagore delivered a lecture at the University, and on the next day Kurt Wolff, Tagore’s German publisher, invited some people from the intellectual élite to a reception at his home. Thomas Mann and his wife Katja attended both the lecture and the reception. Mann noted down in his diary the impressions of this second day:

At 11 drove with K[atja] to K.Wolff’s for R.Tagore’s lecture. Select gathering. The impression of a fine old English lady gained strength. His son was brown and muscular – a masculine type. I was introduced, said ‘it was so beautiful’ and pushed K. forward: ‘my wife who speaks english better than I’. He did not seem to grasp who I was.[11]

What had happened? Tagore’s long robe and his flowing hair had reminded Mann of a “fine old English lady” which was a rather rude remark. When Mann was introduced to Tagore, he avoided a conversation by pushing his wife forward and claiming that she speaks English better than he and hence should be spoken to. After thus studiously avoiding contact with Tagore, Mann should not have been too surprised that the poet did not recognise his German colleague, the famous Thomas Mann. Yet Mann’s pride must have been bruised.

Hermann Hesse (1877-1962) never met Rabindranath Tagore although one would have expected him, more than anybody else, to seek and maintain a contact with the Indian poet. Hesse had been involved with Indian Thought since his childhood. His parents were Protestant Christian missionaries in South India. His maternal grandfather, Heinrich Gundert, had been a pioneering scholar of the Malayalam language and culture. Hesse, like others in his time, naïvely conceived of India as a country of spiritual perfection and angelic human beings. This romantic notion was bound to be shattered when Hesse set out on his one long trip outside Europe which took him to Sri Lanka and Indonesia in 1911. He was unable to set foot on mainland India as due to illness his trip had to be cut short. But he witnessed Hindu and Buddhist culture. Hesse was disillusioned with Asia, but then his expectations had not been realistic. He published his diary notes and returned to his experience again and again in letters, short stories and essays. Slowly, his disappointment transformed itself into a new vision of India which was less idealistic. Formerly, Hesse had believed in the dichotomy of the “spiritual East” and the “materialistic West”. Now he chose to perceive an undercurrent of mysticism in both East and West. He envisioned a spiritual unity encompassing both.

The best-known fruit of Hesse’s Indian experience is his “Indian novel” Siddhartha. When Rabindranath Tagore toured Europe in 1921, Hesse was deeply involved in writing this novel of an Indian spiritual aspirant’s path to fulfilment. He lived in the Ticino mountains in southern Switzerland almost like a hermit. The idea of travelling to Germany or Austria to meet Tagore must have been far from his mind. And yet, Hermann Hesse kept an eye on the intellectual developments of his time. He reviewed three books by Tagore (Gitanjali, The Gardener and The Home and the World) and expressed his views in several letters. The last letter in which Hesse referred to Tagore is from 1957. Hesse was not fascinated by Tagore to the same degree as Stefan Zweig, Romain Rolland and Hermann Keyserling were. Strangely, Hesse considered Tagore’s writing as too European and not of exceptionally high quality, although he did laud the nobility and dream-like beauty of his texts. Hesse did however fully support Tagore’s novel The Home and the World concluding his review with the words: “…the more people read this book the better.”[12]

In his last letter, Hesse commented on Tagore’s “partial eclipse in the West” after the Second World War. Hesse opined that Tagore had been “a fashion” in the 1920s and now had to pay the price for being out of fashion. Yet, in some minds and hearts the effects [of reading Tagore] have lived on and borne fruit, and this continuing influence – impersonal, silent and in no way dependent on fame and fashion – may in the final analysis be more appropriate to an Indian sage than fame or personality cults.[13]

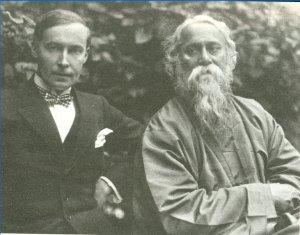

With his publisher Kurt Wolff in 1921

Rabindranath Tagore in Germany Today

We have to return to the question of translations. Translations into German started to appear from 1914 in rapid succession. No sooner did they come out in London, were they taken up by Kurt Wolff. Already in 1921, an eight-volume Collected Works could be published to coincide with Tagore’s first visit to Germany. However, when the devaluation of the German currency set in in 1923, the entire book market began to collapse. Kurt Wolff continued to publish new volumes of translation until 1925, and then he stopped. In 1929, his firm went bankrupt. There were several persons who had prepared translations of Tagore’s works for Kurt Wolff. From among them, Helene Meyer-Franck was the most dedicated and diligent. From 1918, she became the sole translator of Tagore into German. Her husband, Heinrich Meyer-Benfey, and she brought out his Collected Works.

After Kurt Wolff desisted from publishing, a new phase began for Helene Meyer-Franck: she learnt Bengali for the sole purpose of reading Tagore, her “dear Master”, in the original. It was a lonely fight in her small town near Hamburg, as she was virtually on her own. However, she learnt to read Bengali sufficiently well to translate into German three novellas and a collection of poetry. The novellas were published as early as 1930, but they left no visible trace because of the Nazi Reich emerging in 1933. Helene Meyer-Franck had to wait until after the Second World War before she was able to publish her second slim volume. Soon thereafter, first her husband and then she died. As a result, her initiative to translate Tagore directly from Bengali was not continued, and there was nobody to emulated her. In the 1950s, the old translations from English, published in the 1920s, were republished in West-Germany, and in some cases new translations of these weak and flawed English texts came out.

Communist East-Germany had a special relationship with Tagore. The latter’s internationalism endeared him to the regime, and his work was given political weight. Tagore’s books were translated into German in much larger numbers than in the West. Yet, these translations were generally of doubtful quality. Several anthologies contained translations from the English and from the Bengali side by side; other books were translated via Russian. Then there were so-called team-translation, i.e. a Bengali knowing little German and a German knowing little or no Bengali teamed up to produce a translation. None of these methods were at all satisfactory, and they did not serve to enhance Tagore’s reputation as a figure of World Literature. As far as I can see, only one person in erstwhile East-Germany mastered Bengali well enough to produce a competent translation on her own; that was Gisel Leiste, who translated one major novel, Gora.

It was not until the 1980s and 1990s that fresh direct translations were brought out, first by Alokeranjan Dasgupta (one volume) and then by Martin Kämpchen (three volumes). They were brought out by small, specialised or by theological publishers. What Tagore needs acutely, however, are mainstream literary publishers who market his works. This need is soon going to be fulfilled by a volume of love poetry, translated by Martin Kämpchen, brought out (in February 2004) by a premier literary publisher, Insel Verlag, in its series Liebesgedichte. Another publisher, Verlag Artemis & Winkler, is scheduled to bring out a larger volume of Tagore’s Selected Works, edited by Martin Kämpchen, in its series of Classics of World Literature.

I believe that in Germany Tagore’s time has now arrived. Apart from the fact that any great literature has a claim to be noticed and respected throughout the world simply because it is great literature, I wish to identify three areas in which Tagore’s ideas and ideals have a strong relevance for us today:

-

Ecology. – Rabindranath Tagore’s love of nature was inspired by the awareness that all living beings, including animals, trees and plants, are endowed with a soul. On this level of consciousness, human beings are equal with “low” creatures and plants. We are all co-creatures of God’s creation. Accordingly, Tagore’s praise and worship of nature is born of a deep spirit of togetherness and feeling of a creational bond between humans and nature. Such a sense of unity is missing in modern Western ecology. It tends to emphasise the usefulness of nature and the necessity of a natural environment for the practical survival of mankind. Thus, with his poetry and his essays, Tagore can inspire a deeper understanding of and togetherness with the natural environment.

-

Education. – Rabindranath Tagore’s ideas of education continue to be relevant. He wanted to unfold the entire personality through music, songs, dance, theatre, art, contemplation of nature, meditation and social service. The Indian subcontinent has strayed from these ideals, and in Western countries, too, the demons of “usefulness” and “efficiency” have to be tamed by the intentless, playful activity of Tagorean education.

-

International understanding. – Rabindranath Tagore’s deep yearning for harmony among men, achieved through mutual tolerance and simplicity of life, is as worthy of imitation now as it was then. It is not enough to nourish dreams and circulate hopes. Tagore has demonstrated to us how much one inspired human being is capable of achieving among men. Tagore descended from his dreams into reality and gradually worked out an understanding between human beings in his school, his university and his interaction with the wide world.

Rabindranath Tagore Street in Berlin

opened in 1961 (Photo: Christian Zeiske, Berlin)

Notes: Dr Dr Martin Kämpchen is a writer on India and a translator of Tagore from Bengali to German. He lives at Santiniketan, India. For more information visit his website www.martin-kaempchen.com.

- [1] Nirad Chaudhuri: Thy Hand, Great Anarch! India 1921-1952. Chatto & Windus, London 1987, p.596.

- [2] Rabindranath Tagore: Letters to a Friend. Edited by C.F.Andrews. Macmillan, New York 1929, p.171.

- [3] See Rainer Maria Rilke – Lou Andreas Salomé: Briefwechsel. Edited by Ernst Pfeiffer. Insel Verlag, Frankfurt 1975, p.300 (dated 20th September 1913).

- [4] See Kurt Wolff: Briefwechsel eines Verlegers 1911-1963. Edited by Bernhard Zeller and Ellen Otten. Verlag Heinrich Scheffler, Frankfurt 1966, p.136f.

- [5] Op.cit., p.138f.

- [6] Stefan Zweig: Benares: Die Stadt der tausend Tempel. In: Zweig: Begegnungen mit Menschen, Büchern, Städten. S.Fischer Verlag, Berlin/Franklfurt 1956, p.260.

- [7] Kurt Wolff: Briefwechsel eines Verlegers. p. 414.

- [8] Romain Rolland – Stefan Zweig: Ein Briefwechsel 1910-1940. 1st vol. 1910-1923. Verlag Rütten & Loening, Berlin 1987, p.640f.

- [9] Rolland – Zweig: Briefwechsel. 2nd vol. 1924-1940. p.187.

- [10] Thomas Mann: Briefe 1889-1936. Edited by Erika Mann. S.Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt 1961, p.188f.

- [11] Thomas Mann: Tagebücher 1918-1921. Edited by Peter de Mendelssohn. S.Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt 1979, p.529f.

- [12] Vivos Voco (Leipzig), vol. 1, Nov. 1920, p.817.

- [13] Hermann Hesse: Preface. In: Later Poems of Tagore. Translated and with an introduction by Aurobindo Bose. Peter Owen, London 1974, p.7.

- For more comprehensive accounts of Tagore’s impact on the German people, please refer to my books: Rabindranath Tagore and Germany: A Documentation. Max Mueller Bhavan, Calcutta 1991; Rabindranath Tagore in Germany. Four Responses to a Cultural Icon. Indian Institute of Advanved Study. Shimla 1999; My Dear Master. Correspondence of Helene Meyer-Franck / Heinrich Meyer-Benfey and Rabindranath Tagore 1920-1938. Edited by Martin Kämpchen and Prasanta Kumar Paul. Rabindra-Bhavana, Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan 1999.

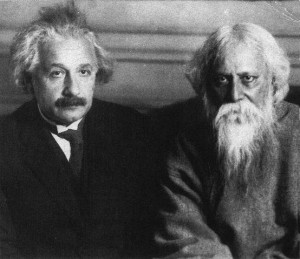

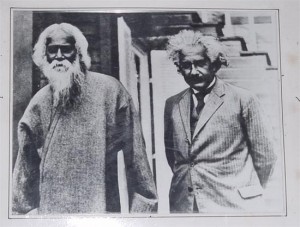

- Tagore meets Einstein:

- Vishva Bharati University: > SCIENCE AND EDUCATION CENTER <

- MAHATMA GHANDI UNIVERSITY<

- GHANDI INSTITUTE FOR NONVIOLENCE

- Meet Rabindranath Tagore, Studies Friends at fb <

- Handwritten Letter in Sweet Memory of Tagore <

- Meet Vishwa Bharati School, friends at fb <

- Meet Mahatma Ghandi, friends, studies at fb <

- Meet Albert Einstein, friends, organisation at fb <

- Meet 100 Years Poetry Society, friends at facebook <

RABINDRANATH TAGORE & AMARTYA SEN.

> AMARTYA SEN. & VISVA-BHARATI UNIVERSITY <

A central university and an institution of national importance

Rabindranath Tagore (Bengali: রবীন্দ্রনাথ ঠাকুর) (May 1861 – 7 August 1941), sobriquet Gurudev, was a Bengali polymath. As a poet, novelist, musician, and playwright, he reshaped Bengali literature and music in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As author of Gitanjali and its „profoundly sensitive, fresh and beautiful verse“, he became Asia’s first Nobel laureate by winning the 1913 Nobel Prize in Literature.

A Pirali Brahmin from Calcutta, Tagore wrote poems at age eight. At age sixteen, he published his first substantial poetry under the pseudonym Bhanushingho („Sun Lion“) and wrote his first short stories and dramas in 1877. Tagore denounced the British Raj and supported the Indian Independence Movement. His efforts endure in his vast canon and in the institution he founded, Visva-Bharati University.

The Right to Education Denied for Rohingya Refugees in Bangladesh

The Right to Education Denied for Rohingya Refugees in Bangladesh https://t.co/lGGqZ9lLBS

— Burma Campaign UK (@burmacampaignuk) 20. Dezember 2018

Further evidence that the Government of Bangladesh has no intention of holding free and fair elections. https://t.co/TmtvVzlvX0

— Toby Cadman (@tobycadman) 22. Dezember 2018

Statistical analysis by the highly credible human rights organisation #Odhikar on the frightening reality in #Banglasesh@GuernicaGroup@GuernicaLaw37pic.twitter.com/gpU9QfRbzz

— Toby Cadman (@tobycadman) 20. Dezember 2018

#Christmas get together at St. Xavier’s College (Autonomous) >> https://t.co/L4qlREti2K

— Mamata Banerjee (@MamataOfficial) 21. Dezember 2018

A worthy read for all who are interested in development & like me love Sen’s work!@clairgammage have you seen this? https://t.co/LIidw4JEFc

— Amy Man (@_Amy_Man) 21. Dezember 2018

Today is the birth anniversary of Srinivasa Ramanujan, mathematical genius. As a tribute to him, this day is also celebrated as National Mathematics Day. Homage to the great genius on this day

— Mamata Banerjee (@MamataOfficial) 22. Dezember 2018

On this day in 1901, Rabindranath’s school Brahmacharyasrama started functioning formally. It later came to be known as Patha-Bhavana. This temple of learning was Tagore’s greatest experiment on creating the ideal human being. My humble homage to the great visionary

— Mamata Banerjee (@MamataOfficial) 22. Dezember 2018

With the chill in the air, it’s now time for festivities to celebrate Christmas and usher in the New Year. My latest FB post >> https://t.co/GfpHxeMK1Rpic.twitter.com/KDVXHZmsPb

— Mamata Banerjee (@MamataOfficial) 21. Dezember 2018

A repressive political environment in #Bangladesh ahead of the Dec 30, elections is undermining the credibility of the process.

Authorities should impartially investigate allegations of election violence and ensure justice for abuses.

New @HRW report:https://t.co/ATOUL3Z92M

— Lotte Leicht (@LotteLeicht1) 22. Dezember 2018

On this day of 1893, that is 121 years ago, Swami Vivekananda had delivered the historic Chicago address.

In his address, Swamiji mesmerized his audience with the electrifying effect of his address, echoing the spiritual and cultural heritage of our country spanning over almost 5000 years.

Swamiji symbolizes positivism. Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore once said, “In him, everything is positive, nothing is negative”. He believed in human dignity. To him, “strength is life, weakness is death”.

We, once again, humbly paid our deepest reverence to Swamiji in today’s occasion and upheld his great spirit and message.

Some pictures of today’s event are uploaded here for all of you to see.

#previous #articles #videos #belurmath

Opening Address of the first World’s Parliament of Religions

On display here from an event at the The Art Institute of Chicago, where this legendary oration was delivered.

150th birth anniversary of Swami Vivekananda

Renaissance of India and The world, an exhibition from 18th February to 14th March 2013 at ICCR, Kolkata.

The Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture, Kolkata and The Indian Council for Cultural Relations, Kolkata present Renaissance of India and The World, Life and Mission of Sri Ramakrishna and Swami Vivekananda, a visual tribute (exhibition) from contemporary artists of India, to commemorate the 150th birth anniversary of Swami Vivekananda from 18th February to 14th March 2013 at Rabindranath Tagore Centre, ICCR, Kolkata from 11 a.m to 7 p.m

Rabindranath Tagore Centre, ICCR,

9A, Ho Chi Minh Sarani, Elgin Kolkata-71, West Bengal

Phone : 033 2287 2680

Website : www.tagorecentreiccr.org

From 18th February to 14th March 2013

Time : 11 a.m to 7 p.m

belurmath.org/news_archives/2013/02/19/renaissance-of-india-a-visual-tribute-exhibition

#previous #articles #videos #ramakrishna #vivekananda #belurmath

MAKERS OF BENGALI LITERATURE : RAMPRASAD SEN

MAKERS OF BENGALI LITERATURE : RAMPRASAD SEN

ACADEMIC PAPER

“O my heart, you know not cultivation.

This human soil is lying fallow

and it would have produced gold if cultivated”

The Indian concept of culture (Kristi, samaskriti) is defined in the above three lines. “The sharpening of human sensitivities, feelings, emotions, and sensibilities through art is one of various ways by which man can ‘cultivate’ the soil of life to make it yield golden harvest in return”. Thus the poet Ramprasad Sen wrote about the main concept of Indian Culture as stated by Niharranjan Roy.

“No flattery could touch a nature so unapproachable in its simplicity. For in these writings we have perhaps alone in literature, the spectacle of a great poet, whose genius is spent in realizing the emotions of a child.Willam Blake, in our own poetry, strikes the note that is nearest his, and Blake is by no means his peer.

“Robert Burns in his splendid indifference to rank, and Whitman in his glorification of common things, have points of kinship with him. But to such radiant white heart of child-likeness, it would be impossible to find a perfect counterpart.”

– Sister Nivedita (Margaret Noble:1867-1911) on Ramprasad Sen

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sister_Nivedita

belurmath.org/kids_section/24-visit-to-niveditas-school

cwsv.belurmath.org/volume_5/questions_and_answers/in_answer_to_nivedita.htm

Ramprasad created a new form of poetry known as ‘Sakta Padabali’ in Bengali, and a new style of singing called ‘Prasadi’. After Ramprasad there was a remarkable outburst of Sakta poetry in Bengal.

His view of life was liberal. He was against racism, castism and untouchability, and generally opposed the Hindu orthodoxies of the conservative society.

Ramprasad believed that there should not be any religious conflict between various sects and cults, since God is one. He wrote, “One in five, five in one mind, should not go into conflicts.” ( ore eke panc, pance ea, non korna sweshasweshi)

Just as the message of Chatanyadeva was spread through his kirtan-singing and dance in the fifteenth century, Ramprasad’s message spread through his songs in the eighteenth century.

The Family

Ramprasad was born in a Baidya (caste of Ayurvedic doctors) familyof West Bengal. Ramprasad’s ancestor Raja Seiharsha Sen, the court physician of Sultan Fakurddin in the fourteenth century, had received the title of Raja from the Sultan.

The family tree:

Sriharsha – Bimal – binayak-Rosh – Narayan – Sangu or Sang – Sarani – Krittibas – Ratnakar – Nityananda – Jaggannath – Jadunandan – Ranjan – Rajiblochon – Jayakrishna – Rameswar – Ramram – Ramprasad.

Ramprasad made reference to his forefathers, especially Krittibas Sen and his father Ramram Sen. The family initially was staying in Dhalahandi in the district of Birbhum, then shifted to Kumarhatta-Halisahar (then in the district of Nadia). His father was a Sanskrit scholar, an Ayurvedician and a poet.

“Tadangaj Ramram mahakobi gunodham

Sada jara sadaya Abhaiya “

Ramprasad also mentioned the scholarly forefathers, who supported many charities.

The family lost their wealth; Ramprasad’s father did not fare well, and died early.

RAMPRASAD’S LIFE AND TIME:

Rising from Ashes – Development as Freedom

3rd International Rice Congress (IRC 2010)

Amartya Kumar Sen, CH (Bengali: , Ômorto Kumar Shen; born 3 November 1933) is an eminent Indian economist and philosopher. He is currently the Thomas W. Lamont University Professor and Professor of Economics and Philosophy at Harvard University. He is also a senior fellow at the Harvard Society of Fellows and a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, where he previously served as Master from the years 1998 to 2004.He is the first Asian and the first Indian academic to head an Oxbridge college. He has been called „the Conscience and the Mother Teresa of Economics“for his work on famine, human development theory, welfare economics, the underlying mechanisms of poverty, gender inequality, and political liberalism. However, he refutes the comparison to Mother Teresa by saying that he has never tried to follow a lifestyle of dedicated self-sacrifice. In 1998, Sen won the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his contributions to work on welfare economics. Amartya Sen’s books have been translated into more than thirty languages. He is a trustee of Economists for Peace and Security. In the year 2006, Time magazine listed him under „60 years of Asian Heroes“and now in 2010 as among the 100 most influential persons in the world.

Sen was born in Santiniketan, West Bengal, the university town established by the poet Rabindranath Tagore, another Indian Nobel Prize winner. His ancestral home was in Wari, Dhaka in modern-day Bangladesh. Rabindranath Tagore is said to have given Amartya Sen his name („Amartya“ meaning „immortal“). Sen hails from a distinguished family: his maternal grandfather Kshitimohan Sen, a close associate of Rabindranath Tagore, was a renowned scholar of medieval Indian literature, an authority on the philosophy of Hinduism, and also the second Vice Chancellor of Visva-Bharati University. Read More HERE

NÄ�landÄ� (Hindi/Sanskrit/Pali: नालंदा) is the name of an ancient center of higher learning in Bihar, India. The site of Nalanda is located in the Indian state of Bihar, about 55 miles south east of Patna, and was a Buddhist center of learning from 427 to 1197 CE. It has been called „one of the first great universities in recorded history.“ Read More: HERE

Sen starts out addressing the question of whether or not freedom is conducive to development. He feels that such a question is at best defectively formulated, for reasons given below. Sen ponders over how freedom is often dissociated from development, and considered a pleasant consequence thereof. However, Sen counters that freedom in itself should be the goal of development, and it is both constitutive and instrumental to development.

He makes the argument that freedom (political, economic or societal) is central to achieving development; while freedom may result from such development, it would be unwise to ignore the inverse relationship, and true development will only happen through the proliferation of such freedoms. Furthermore, if the definition of development is to move beyond GNP and include freedom, unfree societies aren’t really quite developed.

Sen also argues against the “Lee Hypothesis”, named after the first Prime Minister of Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew. The idea behind the “Lee Hypothesis” is that democracy and freedom are luxuries that only developed societies can afford, and to become developed, less-developed societies will need to push forth agendas that may be at odds with democracy and freedom. Furthermore, a more ardent view would be that “non-democratic systems are better in bringing about economic development” for such societies.

In the same vein, he also takes to task the interpretation that “Asian Values” are inherently unsuitable and unfit for democracy, where Asia is defined not by region but through culture. The argument goes that discipline and obedience are critical traits to the Asian cultural psyche and as such, democracy is at odds with such a principle. This particular notion has had the unfortunate reputation of being exploited by authoritarian governments across Asia.

Sen counters both the “Lee Hypothesis” and the “Asian Values” argument by offering the example of the biggest democracy in Asia — India. While India has made several economic mistakes through the years, the fact that it continues to be free democracy has helped its economy grow while preserving the freedoms of its citizens. Sen also counters that the “Asian Values” argument isn’t necessarily unique to Asia, and that even within Asia, there have been differing schools of thought, including those that question blind allegiance to the state. And of course, this book also touches upon Sen’s (now-famous) insight on famines and democracies.

He argues that famines are not necessarily caused by lack of declines in food production but rather due to instability in the political, economic, or societal structures that leaves sections of the population unable to fend for themselves.

Sen further proposes that countries that are “free” in the economic sense would have citizenry with a consistent income flow, and this income can be used to borrow or import basic necessities in times of need.

In Development as Freedom Amartya Sen explains how in a world of unprecedented increase in overall opulence millions of people living in the Third World are still unfree. Even if they are not technically slaves, they are denied elementary freedoms and remain imprisoned in one way or another byeconomic poverty, social deprivation, political tyranny or cultural authoritarianism. The main purpose of development is to spread freedom and its ‚thousand charms‘ to the unfree citizens. Freedom, Sen persuasively argues, is at once the ultimate goal of social and economic arrangements and the most efficient means of realizing general welfare.

Social institutions like markets, political parties, legislatures, the judiciary, and the media contribute to development by enhancingindividual freedom and are in turn sustained by social values. Values, institutions, development, and freedom are all closely interrelated, and Sen links them together in an elegant analytical framework. By asking ‚What is the relation between our collective economic wealth and our individualability to live as we would like?‘ and by incorporating individual freedom as a social commitment into his analysis Sen allows economics once again, as it did in the time of Adam Smith, to address the social basis of individual well-being and freedom. But at the end of the day, Sen concludes that true development cannot be measured through mere tangibles (e.g. GNP). Freedom remains the only true measure of development, and when there is freedom, development will follow.

„Poverty is perpetuated by our Institutions“ http://wn.com/amartya_sen_think_and_act http://www.theendofpoverty.com

Amartya Sen, Born in West Bengal, India, he has a patrician style: occasionally loquacious, often ironic, usually genial, always brilliant. Crucially, at the other, older Cambridge, Sen studied philosophy and economics. He has always concerned himself as much with moral as material problems. In his most famous book, Poverty and Famines — inspired by the Bengal famine of 1943, which he witnessed as a boy — he asked how people could starve when food was available. The answer was that the poor simply lacked the capability to buy it. On these and other issues, the argumentative Indian has persuaded.

His notion of measuring human development is now central to the work of the U.N. and the World Bank. As a result, Sen’s influence extends all the way down to what another great economist has called „the bottom billion.“ http://www.time.com/time/specials.html

Amartya Sen, the World Bank, and the Redress of Urban Poverty: A Brazilian Case Study – While there is some suggestion of a re-orientation in the World Bank’s income-cantered conceptualization of poverty to one based on Amartya Sen’s concept of ‚development as freedom‘, it is hard to uncover definitive evidence of such a re-orientation from a study of the Bank’s urban programmes in Brazil. This paper attempts an application of Sen’s capability approach to the problem of improving the urban quality of life, and contrasts it with the World Bank’s approach, with specific reference to a typical squatter upgrading project in Novos Alagados in Salvador da Bahia, Brazil. Click here

A GLOBAL EDUCATION PROGRAM – THE CASE OF NOVOS ALAGADOS, Salvador Bahia, Brazil – In development programs it is fundamental to set upmalliances finalised towards the common objective: a partnership between subjects to set synergies and large amounts of resources into motion. The role of AVSI was exactly the one of aggregating and involving local administrations, social forces, international institutions, according to their respective roles, to meet the needs confronting them, for the common good.

The program had the peculiarity to have a large wealth of resources converge on the territory, through the partnership network, thus opening up the area towards the world and the world towards the area.

India’s lost Buddhist university to rise from ashes – Indian academics have long dreamt of resurrecting Nalanda University, one of the world’s oldest seats of learning which has lain in ruins for 800 years since being razed by foreign invaders.

Now the chance of intellectual life returning to Nalanda has come one step closer after the parliament in New Delhi last month passed a bill approving plans to re-build the campus as a symbol of India’s global ambitions.

Historians believe that the university, in the eastern state of Bihar, once catered for 10,000 students and scholars from across Asia, studying subjects ranging from science and philosophy to literature and mathematics.

Founded in the third century, it gained an international reputation before being sacked by Turkic soldiers and its vast library burnt down in 1193 — when Oxford University was only just coming into existence.

Piles of red bricks and some marble carvings are all that remain at the site, 55 miles (90 kilometres) from Bihar’s state capital of Patna.

„Nalanda was one of the highest intellectual achievements in the history of the world and we are committed to revive it,“ said Amartya Sen, the renowned economist and Nobel laureate who is championing the project.

„The university had 2,000 faculty members offering a number of subjects in the Buddhist tradition, in a similar way that Oxford offered in the Christian tradition,“ he said at a promotional event in New Delhi.

The new Nalanda University has been allocated 500 acres (200 hectares) of land near its original location, but supporters who have lobbied for the cause for several years admit that major funds are needed if Nalanda is to rise from the ashes.

„Income from a number of villages, and funds from kings, supported the ancient Nalanda. Now we have to look for donations from governments, private individuals and religious groups,“ said Sen. Whatever the financial position, the need for more high-level educational institutes in India is clear. Click HERE

- DEVELOPMENT AS FREEDOM <

- Naropa & Nalanda University <

- Jain Tradition & Nalanda University <

- http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economics/sen-autobio.html

- http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/laureates/2006/yunus.html

- http://www.avsi.org/NovosAlagados.pdf

- Meet IRRI Rice Research Center, studies, friends, fans at fb <

- Meet Yunus Center, studies, friends, fans at fb <

- Meet Human Rights Watch, friends, fans at fb <

- Meet Transparency International, friends, fans at fb <

- Meet FAIR TRADE, friends, fans at fb < & www.ethicalconsumer.org

- Meet International Year of Biodiversity, friends, fans at fb <

- Meet Support UN Resolution on the Right to Water and Sanitation <

- Meet UN Millennium Development Goals, friends, fans at fb <

- Meet International Year of Biodiversity, friends, fans at fb <

- Meet COP16 to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change at fb <

CELEBRATION OF TAGORE´s 150th BIRTHDAY

TAGORE, Crisis in Civilization , There are Real Alternatives. A.E. Inst.

Rabindranath Tagore’s Birthday

Rabindranath Tagore (7 May 1861 – 7 August 1941), sobriquet Gurudev, was a Bengali polymath. As a poet, novelist, musician, and playwright, he reshaped Bengali literature and music in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As author of Gitanjali and its „profoundly sensitive, fresh and beautiful verse“, in 1913 being the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize in Literature, Tagore was perhaps the most important literary figure of Bengali literature. He was a mesmerising representative of the Indian culture whose influence and popularity internationally perhaps could only be compared to that of Gandhi, whom Tagore named ‚Mahatma‘ out of his deep admiration for him. A Pirali Brahmin from Kolkata, Tagore was already writing poems at age eight.At age sixteen, he published his first substantial poetry under the pseudonym Bhanushingho („Sun Lion“) and wrote his first short stories and dramas in 1877. Tagore denounced the British Raj and supported independence. His efforts endure in his vast canon and in the institution he founded, Visva-Bharati University. Read More: > HERE <

Albert Eintstein Institute, About Our Name – Albert Einstein was deeply concerned about war, oppression, dictatorship, genocide, and nuclear weapons. He was willing to explore new approaches to confronting these problems of political violence, although he was not always happy with the choices available to him. At various times he was a war resister, a supporter of the war against the Nazi system, and an advocate of world government. In his later life, he became enormously impressed with the potential of nonviolent struggle. In 1950, he remarked on a United Nations radio broadcast that, „On the whole, I believe that Gandhi held the most enlightened views of all the political men in our time….“

Today, the Albert Einstein Institution continues work on that aspect of Einstein’s thought, examining the potential of nonviolent struggle to resolve the continuing problems of political violence.

Applications of Nonviolent Action (AHIMSA) – Nonviolent struggle can be used in a variety of circumstances for a variety of objectives. These include:

Dismantling dictatorships, Blocking coups d’état, Defending against foreign invasions and occupations, Providing alternatives to violence in extreme ethnic conflicts, Challenging unjust social and economic systems, Developing, preserving and extending democratic practices, human rights, civil liberties , and freedom of religion, Resisting genocide

More information can be found about each of these applications in the > publications section < of our web. site.

K. J. Yesudas (Carnatic Music) www.hrw.org

Yama, niyama, asana, pranayama, pratyahra, dharana, dhyana and samadhi are the eight limbs of yoga . Ahimsa, satya, asteya, bramacharya and aparigraha are the five yamas – The yoga sutras of Patanjali, 2.30-31

In the classical yoga system described by Patanjali more than two thousand years ago, the first stage (or limb, as they are generally called) of yoga is Yama (ethical disciplines) and of these, Ahimsa is the first. (The ethical Do´s and Don´ts or commandments for a propper way of life.)

In short, according to Patanjali, ahimasa, non-violence or, as Desikashar defines it, “Consideration for all living creatures, especially those who are innocent, in difficulty or worse off than we are” should be the very beginning of any yoga practice.

Sadhana : the realisation of life by Rabindranath Tagore Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) was a Bengali poet, philosopher, artist, playwright, composer and novelist. India’s first Nobel laureate, Tagore won the 1913 Nobel Prize for Literature. He composed the text of both India’s and Bangladesh’s respective national anthems. Tagore travelled widely and was friends with many notable 20th century figures such as William Butler Yeats, H.G. Wells, Ezra Pound, and Albert Einstein. While he supported Indian Independence, he often had tactical disagreements with Gandhi (at one point talking him out of a fast to the death). His body of literature is deeply sympathetic for the poor and upholds universal humanistic values. His poetry drew from traditional Vaisnava folk lyrics and was often deeply mystical.

Sadhana is a collection of essays, most of which he gave before the Harvard University, describing Indian beliefs, philosophy and culture from different viewpoints, often making comparison with Western thought and culture. (Summary by Peter Yearsley/Wikipedia)

CONTENTS: I. THE RELATION OF THE INDIVIDUAL TO THE UNIVERSE, II. SOUL CONSCIOUSNESS,III. THE PROBLEM OF EVIL, IV. THE PROBLEM OF SELF, V. REALISATION IN LOVE, VI. REALISATION IN ACTION, VII. THE REALISATION OF BEAUTY, VIII. THE REALISATION OF THE INFINITE

FULL TEXT AT PROJEKT Gutenberg < TAGORE AT SACRED TEXT´s < ( Gitanjali [1913], Saddhana, The Realisation of Life [1916] The Crescent Moon [1913], Fruit-Gathering [1916], Stray Birds [1916], The Home and the World [1915], Thought Relics [1921] Songs of Kabîr[1915])

Project Gutenberg, abbreviated as PG, is a volunteer effort to digitize and archive cultural works, to „encourage the creation and distribution of eBooks.“ Founded in 1971 by Michael S. Hart, it is the oldest digital library. www.gutenbergnews.org & www.gutenberg.org

- Tagore, Gandhi and India today <

- VISVA-BHARATI , RABINDRANATH TAGORE – YOGAH ,SCIENCE, POETRY <

- Vedanta, Quantum Physics & Erwin Schrödinger <

- AHIMSA IN YOGA, MUSIC AND SPIRITUALITY <

- The Universal Declaration of Human Rights < , United Nations: Human Rights <

- Meet Human Rights Watch, friends at fb <

- Meet Project Gutenberg, Online Library , studies, friends at fb <

- M.K. Gandhi Institute for Nonviolence, studies, friends at fb <

- Meet The Nobel Women’s Initiative, studies, friends at fb <

- Meet Council for a Parliament of the World’s Religions (CPWR), friends, fans at fb <

Ghandi Institute:Dialogue led by local teens

I.A.S.E. UNIVERSITY – Ghandi Vidya Mandir

Frederick Douglass Institute for African and African-American Studies

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (Hindi: मोहनदास करमचंद गाँधी, Gujarati: મોહનદાસ કરમચંદ ગાંધી, pronounced [moːɦən̪d̪aːs kərəmʨən̪d̪ ɡaːn̪d̪ʱiː] ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948) was the pre-eminent political and spiritual leader of India during the Indian independence movement. He was the pioneer of satyagraha—resistance to tyranny through mass civil disobedience, a philosophy firmly founded upon ahimsa or total nonviolence—which led India to independence and inspired movements for civil rights and freedom across the world. Gandhi is commonly known around the world as Mahatma Gandhi ([məɦaːt̪maː]; Sanskrit: महात्मा mahÄ�tmÄ� or „Great Soul“, an honorific first applied to him by Rabindranath Tagore), and in India also as Bapu (Gujarati: બાપુ, bÄ�pu or „Father“). He is officially honoured in India as the Father of the Nation; his birthday, 2 October, is commemorated there as Gandhi Jayanti, a national holiday, and worldwide as the International Day of Non-Violence. (ahimsa) Read More: > HERE <

Welcome to the M.K. Gandhi Institute of Nonviolence, founded by Arun Gandhi, grandson of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. The Institue has been housed at the University of Rochester since June 2007.

The M.K. Gandhi Institute for Nonviolence is located at the University of Rochester in Rochester, NY. We are dedicated to carrying out the principles of Mohandas K. Gandhi. Learn more about Gandhi!

Working in partnership with University of Rochester students and other organizations, we help local children learn about alternatives to conflict, teach nonviolence through service projects, plant food and flower gardens on and off the University of Rochester campus, tend sections of the nearby Genesee River, participate in urban agriculture to reduce hunger and create jobs, and support a grassroots movement to make Rochester a national leader in restorative justice.

We strive to identify, support and create projects and social systems that value all lives equally and where means and ends are understood to be inextricably linked.

Teen and adult facilitators are from Teen Empowerment: an organization which inspires young people, and the adults who work with them, to think deeply about the most difficult social problems in their communities, and gives them the tools they need to work with others in creating significant positive change. (Sponsored by Community Service Network, Rochester Community Center for Leadership, Office of Minority Student Affairs, and Fredrick Douglas Institute.)

Date: Friday, April 16, 2010

Time: 3:00pm – 5:00pm

Location: 108 Goergen (UR River Campus)

The Real Meaning of „ADVAITA“, Vedanta

> INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS OF VEDANTA <

> Sri Ramana Maharshi Ashram, Message No.141 <

> Advaita Vedanta, Vivekananda, Ramakrishna <

Vedanta (Devanagari: वेदान्त, VedÄ�nta) was originally a word used in Hindu philosophy as a synonym for that part of the Veda texts known also as the Upanishads. The name is a sandhied form of Veda-anta = „Veda-end“ = „the appendix to the Vedas“. By the 8th century CE, the word also came to be used to describe a group of philosophical traditions concerned with the self-realisation by which one understands the ultimate nature of reality (Brahman). The word Vedanta teaches that the believer’s goal is to transcend the limitations of self-identity. Vedanta is not restricted or confined to one book and there is no sole source for Vedantic philosophy. Vedanta is based on two simple propositions: 1.) Human nature is divine. 2.) The aim of human life is to realize that human nature is divine. READ FULL ARTICLE > HERE <

Advaita Vedanta (IAST Advaita VedÄ�nta; Sanskrit अद्वैत वेदान्त; is a sub-school of the VedÄ�nta (literally, end or the goal of the Vedas, Sanskrit) school of Hindu philosophy. Other major sub-schools of VedÄ�nta are Dvaita and ViśishṭÄ�dvaita. Advaita (literally, non-duality) is a monistic system of thought. „Advaita“ refers to the identity of the Self (Atman) and the Whole (Brahman).

The key source texts for all schools of VedÄ�nta are the Prasthanatrayi—the canonical texts consisting of the Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita and the Brahma Sutras. The first person to explicitly consolidate the principles of Advaita Vedanta was Adi Shankara while the first historical proponent was Gaudapada, the guru of Shankara’s guru Govinda Bhagavatpada. READ FULL ARTICLE >HERE <

The Advaita Vedanta Anusandhana Kendra (Advaita Vedanta Research Center) is dedicated to increasing knowledge of the tenets of Advaita Vedanta–a philosophy and religion based on the Vedas that teaches the non-duality of the individual soul and God–as expressed by its foremost exponent Shankaracharya (whose picture you see above) and the unbroken succession of teachers descended from him.

Die Philosophenschulen – Im Anschluss an die vedische Zeit entstanden in Indien verschiedene Philosophenschulen. Einige davon akzeptierten die Veden als Autorität, diese Schulen werden als orthodox bezeichnet. Andere Schulen lehnten die Veden ab. Dies sind der Buddhismus, die Jaina-Religion und die Charvakas (Materialisten). Von den orthodoxen Schulen sind in spiritueller Hinsicht interessant:

-

Samkhya – diese Schule versucht die Welt möglichst logisch zu erklären.

-

Yoga – baut auf den Theorien des Samkhya auf und liefert eine praktische Methode.

-

Tantra – baut auf den Theorien des Vedanta, bzw. Advaita auf und liefert eine praktische Methode.

-

Vedanta – Vedanta, wörtlich Veda-Ende, bezieht sich also auf die Upanishaden. Deren Botschaft fasste Badarâyana in seinen Vedanta-Sutras äußerst knapp zusammen.

International Vedanta Society – Vedanta is a spiritual science that shines light upon our very nature, illuminating the truth that we are all One with God, and that our souls are the divine manifestation of existence, knowledge, and bliss.

This truth is veiled beneath false beliefs that would limit us through fears, doubts and weaknesses. Vedanta uproots this ignorance thereby inviting us to embrace the truth of who we are (omnipresent, omniscient and omnipotent). This universal truth is available to any seeker regardless of religion, culture, or sex.

The core and founder of IVS is Bhagavan. His deep love and concern for others inspired him to pioneer many social welfare activities, even as a child. His passionate quest for truth led him to the holy feet of his master Swami Pavitrandaji Maharaj, and through his teachings, Bhagavan sank into the depths of Nirvikalpa Samadhi, (realization of the Supreme Self) in 1984, and Mahabhava (Supreme Godhood) in 1987. Since that time, Bhagavan has strived to help others attain and taste supreme joy and love.

The life and words of Bhagavan, through truth and love incarnate, offer a shelter for the tired and weary, who return home with peace, bliss, confidence, hope, and life.

The International Vedanta Society (IVS), was formed on November 19th, 1989 through the divine will manifesting in Bhagavan. Commencing its journey from Guwahati in the North Eastern part of India, the society has within a short span spread to various countries throughout the world, through its mediums of love and service. Realization of the Self or God is the key note of IVS. Its members and well-wishers strive continuously to radiate eternal love and bliss.

International Congress of Vedanta was established in 1986 by Professor S.S. Rama Rao Pappu in the Department of Philosophy, Miami University in order to bring together scholars specializing in Indian Philosophies and Religions from all over the world for the study and exchange of ideas and to promote research. In the past eighteen years, fifteen conferences were organized, ten of them at Miami University and five conferences were organized abroad – in Port-of-Spain, Trinidad, and in Rishikesh (Himalayas), Madras, Hyderabad and Visakhapatnam, India.

Centennial celebrations of great Indian philosophers were also held during the Vedanta Conferences – e.g. birth centennial of S. Radhakrishnan in 1988, 1200th anniversary of Sri Sankaracharya in 1990, centennial of Swami Vivekananda’s sojourn to America and his participation in the Parliament of World’s Religions in Chicago in 1992, birth centennial of J. Krishnamurti in 1995, and the 700th anniversary of sanjeewan Samadhi of Sri Jnaneswara in 1996.

Vedanta Congress welcomes for presentation in the conferences research papers in all areas of Indian philosophies and religions.

Though the first Vedanta Conference began with a narrowly focused group for the study of Vedantic texts and their interpretation, the scope of the Vedanta Congress was expanded during the years to include:

- (a) all major schools of Vedanta (Advaita, Visistadvaita, Dvaita, Suddhadvaita, etc.), Hindu, Buddhist and Jaina Darsanas, Epics, Puranas and Dharma Sastras

- (b) applied Indian philosophy, dealing with contemporary issues like abortion and euthanasia, war and peace, caste and race, karma and cloning

- (c) Indian philosophical implications of recent developments in mathematics, life sciences, cognitive science, etc.

-

Vedanta Articles Dein Ayurveda Net > HERE <

-

COMPLETE WORK OF RAMAKRISHNA AND VIVEKANANDA (free) downloads: www.ramakrishnavivekananda.info

-

Swami Vivekananda´s > SPEECH AT CHICAGO < at the PARLIAMENT OF WORLDRELIGIONS at Chicago in 1893.

- Read Fundamental Concepts of Vedanta here:

Evening about Tagore Culture Prize 2009

German President at Göthe Institute Dehli

> Göthe Institute in New Dehli <

> PRESSEMITTEILUNG TAGORE KULTURPREIS 2009 <

> Deutsch Indische Ges. Tagore Kulturpreis <

Rabindranath Tagore (Bengali: রবীন্দ্রনাথ ঠাকুর) (7 May 1861 – 7 August 1941),sobriquet Gurudev,was a Bengali polymath. As a poet, novelist, musician, and playwright, he reshaped Bengali literature and music in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As author of Gitanjali and its „profoundly sensitive, fresh and beautiful verse“, being the first non-European to win the 1913 Nobel Prize in Literature, Tagore was perhaps the most important literary figure of Bengali literature and a mesmerising representative of the Indian culture whose influence and popularity internationally perhaps could only be compared to that of Gandhi whom Tagore named ‚Mahatma‘ out of his deep admiration for him.Read More: > HERE <

On 10th October 2009, the German musician and author Peter Pannke along with Dieter B. Kapp received the prestigious Rabindranath Tagore Culture Prize 2009 from the Indo-German Society in Stuttgart.

This award acknowledges over 30 years of Pannke’s commitment and dedication as an ambassador of Indian traditions in Germany and as a promoter of musical dialogues between the two countries. To mark this occasion, the Goethe-Institut has invited the renowned Indologist to a festive program at the Max Mueller Bhavan. The program will include conversations about his recently published books ‘Singers Die Twice’ and ‘Dreamtalker’ as well as readings from these books. Strains from traditional Dhrupad music will conclude the evening.

The poet, Ashok Vajpeyi, will inaugurate the program with a speech in honour of Peter Pannke. Other participants in this event: Sanjeev Gupta (Translator), Dhritabrata Bhattacharjya Tato (Publisher Daastaan), Druphad singer Prashant Kumar Mallik accompanied by his music ensemble.

Filmclip: „Obsession“ by Troubadour United

Peter Pannke studied Sinology, Indology, comparative religious studies and Musicology. He travelled for many years through the Near East, North Africa, Pakistan and India, before he made a name for himself as a radio broadcaster, sound artist and as leader of the band Troubadours United. He is a composer and musician and has produced over eighty CDs/LPs. He is also an author of reportages, illustrated books and poetry. His book „Dreamtalker – Songs, Poems, Essays“ was released in January 2010 in Delhi by Dastaan Publishers. The English translation of his highly acclaimed travelogue „ Singers Die Twice“will be published in India this autumn.

Singer, Dreamer and Storyteller:

An evening with Rabindranath Tagore Culture Prize winner Peter Pannke

Literature / Music

Thursday, 04.03.10, 7.00 p.m.

Siddhartha Hall, Goethe-Institut/Max Mueller Bhavan

Related link:

Press release announcing the Rabindranath Tagore Culture Prize winner for 2009 deutsch

Meet ALL Rabindranath Tagore, Friends, Studies, Groups at fb <

THE EAST MEETS WEST MUSIC INC.

http://eastmeetswestmusic.com/

> Ali Akhbar College of Music, LAYA Project <

> GHARANA – Benares Music Academy <

„There is something beautiful about the stage. There is a performer and there is an audience. Nothing is in the way. The sound remains pure and unburdened by things like marketing and distribution. My hope is for this label to be more like a stage and less like the music business as I have experienced it.”

–Ravi Shankar

Ravi Shankar (Bengali: রবি শংকর; born 7 April 1920), often referred to by the title Pandit, is an Indian sitarist and composer. He has been described as the most well known contemporary Indian musician by Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart.Shankar was born in Varanasi and spent his youth touring Europe and India with the dance group of his brother Uday Shankar. He gave up dancing in 1938 to study sitar playing under court musician Allauddin Khan. After finishing his studies in 1944, Shankar worked as a composer, creating the music for the Apu Trilogy by Satyajit Ray, and was music director of All India Radio, New Delhi, from 1949 to 1956. Read more: > HERE <

WELCOME – The Ravi Shankar Foundation proudly announces the launch of East Meets West Music. EMW Music is a listener’s passport to the sitar master’s personal archive of thousands of hours of live performance audio, film footage, interviews, and studio masters. By making personally selected source material from this collection available, Ravi Shankar hopes to bridge any divide between his recorded music and his audience. EMWMusic also provides a vibrant space for new artists, projects, and collaborations. We are thrilled to begin this journey with our long time supporters and new fans alike.

The aim of the Benares Academy is to:

- Establish a school for the teaching of Indian Classical music in the traditional Benaras Gharana style;

- Provide scholarships to children to assist them in their learning of this musical style;

- Create opportunities for students and young artists to develop their potential through study and performance;

- Provide right livelihood for qualified and dedicated teachers.

For this purpose, the Mishra family purchased land in Benares on which to build a residential music school. The construction of the building took around three years to be completed and now the Academy is a well-structured place to receive students from all over the world.

For foreign students, who are committed to studying seriously, the Academy opens its doors providing them with all facilities needed such as a proper music hall, nice rooms with or without toilet attached, spacious kitchen, mineral water filter and dining room, apart from a safe and peaceful atmosphere. Moreover, it is located five minutes walk from the Ganga River.

The mission of the Ali Akbar College of Music is to teach, perform and preserve the classical music of North India, specifically the Seni Baba Allauddin Gharana (tradition), and to offer this great musical legacy to all who wish to learn. The Ali Akbar College of Music offers education in the classical music of North India at the highest professional level. Our primary instructors are the internationally recognized sarode Maestro Ali Akbar Khan and the master of percussion Pandit Swapan Chaudhuri, from whom our students learn the necessary musical skills, knowledge and understanding to contribute significantly to musical life.

At a dargah (Islamic shrine) situated in the south-east part of India, the singers sing devotional songs in the Qawwali style, with percussion accompaniment. The lyrics are a mix of the local south Indian language, Tamil and Arabic, while the music style is that of northwestern India.

These artists are featured in the award-winning music documentary LAYA PROJECT (www.layaproject.com), and have also released a full album called NAGORE SESSIONS, available at www.earthsync.com

A tribute to the resilience of the human spirit, LAYA PROJECT is a documentary about the lives and music culture of coastal and surrounding communities inthe 2004 tsunami-affected regions. Some of these performances are rare, and documented for the first time.

Sree Debasish Dass (Pintoo) Born in a very tradtional musical familly on May day, Sree Debasish Dass has carved a special niche for himself in the world of Tabla, the king of Indian percussion instruments. He was initiated into Tabla at the tender age of five by his beloved father Late Dilip Kumar Pandit a highly acclaimed Tabla player of Farukkabad Gharana.

True to his date of birth, which symbolises sincere labour, > Debasish < (popularly known as Pintoo) put in years of relentless effort and unfailing dedication to master the art of playing Tabla. He completed his graduation from the world famous Visva-Bharati University founded by the great > Rabindra Nath Tagore < . Thereafter he plunged fully into the subtle complexities Tabla and completed his Diploma in music, Bachelor and Master degree in Tabla.

http://swara.at/ (Plattform f. Indische Musik und Tanz in Österreich)

http://www.alankara.com/ (Ver. z. Förd. d. Ind. Musik ,Kunst in Wien)

http://www.indigenouspeople.net/taino.htm (Ind. Friends, Haiti)

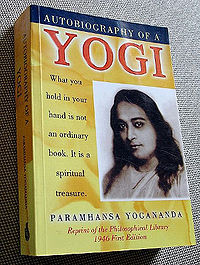

DIE AUTOBIOGRAPHIE EINES YOGI´s

> PARAMAHANSA AND KRIYA YOGA <

> UNESCO, PURANAS, KRIYA YOGA <

> GUIDANCE ON THE ECONOMIC CRISES <

> PARAMAHANSA´s VIEW ON THE 4 GOSPEL´s <

> INTERNATIONAL HEADQUATER BUILDING <

Paramahansa Yogananda (Bengali,Pôromohôngsho Joganondo, Sanskrit: परमहंस योगानंद Paramahaṃsa YogÄ�naṃda; January 5, 1893–March 7, 1952), born Mukunda Lal Ghosh (Bengali:, Mukundo Lal Ghosh), was an Indian yogi and guru who introduced many westerners to the teachings of meditation and Kriya Yoga through his book, Autobiography of a Yogi. Read More: > HERE <

In 1946, Paramahansa Yogananda (January 5, 1893–March 7, 1952), published his life story, Autobiography of a Yogi, which introduced many westerners to meditation and yoga. It has since been translated into 25 languages, and the various editions published since its inception have sold over a million copies worldwide. The book describes Yogananda’s search for a guru, and his encounters with leading spiritual figures such as Therese Neumann, the Hindu saint Sri Anandamoyi Ma, Mohandas Gandhi, Rabindranath Tagore, Nobel Prize-winning physicist Sir C. V. Raman, and noted American plant scientist Luther Burbank, to whom it is dedicated. Read more: > HERE <

Paramahansa Yogananda – Wissenschaftliche Heilmeditationen:

Schon lange bevor Heilmeditationen in solch unterschiedlichen Bereichen wie Krankenhäusern und in der Rehabilitation, im Sport und in den Büros der Manager breite Anwendung fanden, hatte der berühmte Mystiker Paramahansa Yogananda durch sein umfassendes Verständnis die tiefgeistigen Grundlagen gelehrt, welche diese althergebrachte wissenschaftliche Methode so außerordentlich wirksam machen.

In diesem Buch enthüllt er die verborgenen Gesetze, die man sich zunutze machen kann, um seine Gedankenkraft konzentriert einzusetzen – nicht nur um den Körper zu heilen, sondern auch um Hindernisse zu überwinden und sein Leben erfolgreich zu gestalten. Dieser Band enthält neben ausführlichen Anleitungen Heilmeditationen verschiedener Art: zur Heilung des Körpers, zur Entwicklung von Selbstvertrauen, zur Erweckung von Weisheit, zur Überwindung schlechter Gewohnheiten – und zu vielen anderen Zwecken.

-

143 Seiten, Paperback:

-

www.yoga-aktuell.de : > DIE WISSENSCHAFTLICHEN HEILMETHODEN <

> Meet Paramahansa Yogananda friends, groups, studies at fb <

VISVA-BHARATI UNIVERSITY, TRUST

RABINDRANATH TAGORE – YOGAH,SCIENCE POETRY

INT. CONFERENCE ON GLOBAL CLIMATE CHANGE

Visva Bharati University, Santiniketan (বিশ্বভারতী বিশ্ববিদ্যালয়) is a Central University for research and teaching in India, located in the twin town of Santiniketan and Sriniketan Indian state of West Bengal. It was founded by Rabindranath Tagore who called it Visva Bharati, which means the communion of the world with India. In its initial years Tagore expressed his dissatisfaction with the word ‚university‘, since university translates to Vishva-Vidyalaya, which is smaller in scope than Visva Bharati. Until independence it was a college. Soon after independence, in 1951 the institution was given the status of a university, and was renamed Visva Bharati University.

The origins of the university date back to 1863 when Maharshi Debendranath Tagore, himself the zamindar of Silaidaha in East Bengal, bought a tract of land from the zamindar of Raipur, which was a neighbouring village not too far from present day Santiniketan and set up an ashram at the spot that has now come to be called chatim tala at the heart of the town. The ashram was initially called Brahmacharya Ashram, which was later renamed Brahmacharya Vidyalaya. It was established with a view to encourage people from all walks of life to come to the spot and meditate. In 1901 his youngest son Rabindranath Tagore established a co-educational school inside the premises of the ashram. Read More > here <

VISHWABHARATI TRUST:

Project Description

The > Vishwabharati Trust < is located at Anavatti, a rural area belonging to Karnataka,India. The place is about 500 kms from Bangalore, well connected by road, amidst beautiful Malnad greenary.

The Vishwabharati Trust was started on 6 th October, 1997 to provide education to poor and physically handicapped children. The trust is presently running a school and 140 deserving children are now studying.

The main objectives of the Vishwabharati Trust are as follows:

1. To make the children self dependent.

2. To make the children aware of our rich culture and heritage.

3. To develop fine and strong character.

4. To develop the children in sports and extra curricular activities

Organization Description

Objectives:

To establish and maintain educational institutions from pre-primary to post graduation level, including professional, technical, vocational and training institutes of any kind and moral training for the benefit of the public in rural community particularly.

> Meet Rabindranath Tagore Fans at facebook <

> Meet handwritten Letter In Sweet Memory of Tagore at facebook <

> Meet STOP GLOBAL WARMING GROUPS AND STUDIES at facebook <

> Meet Vishva-Bharati Public School at facebook <

Mamata Banerjee @MamataOfficial

Mamata Banerjee @MamataOfficial